The Fortunes of Favell

“What’s in a name?”

Shakespeare – Romeo and Juliet

“John Rivers, a strangers child, found in the river, from which he took his surname”

Stratford St Mary, Suffolk – Baptismal Register

This extract from an eighteenth century parish register is an unusual example of obtaining a surname. Most Englishmen had such an addition to their Christian names by the early fourteenth century. As in John Rivers case they were chosen and imposed by neighbours or carers. In early times the number of Christian names was very limited and as the population grew, extra names were essential to distinguish all the Toms, Dicks and Harrys one from another.

Early surnames were not passed on automatically at first from Father to Son. They described one unique individual, but gradually the advantage of surnames was realised for proving descent in official documents such as ownership of land. Genealogies could be traced over hundreds of years allowing inheritance of land or property to be better regulated.

Thus a gradual process of adoption of ‘surnames’ (extra names) began, starting after the Norman Conquest of England in 1066 for the Nobility and Gentry. Most ordinary English people had hereditary surnames by the end of the fourteenth century, as did the Favells.

Villagers who lived for several generations in the same house or locality often inherited a surname linking them with the place name, or some natural feature of the landscape, as in ‘John of Tilbrook’ or ‘Henry Brook’. Men who were on the move often retained the name of their birthplace as their surname, which helps family historians to this day.

Skilled craftsmen or traders were known by their professional names, Miller, Carpenter, Smith. Nicknames have always been popular and medieval people loved to label their enemies with rude or uncomplimentary surnames as our family must ruefully admit. The earliest man in our family to bear the name Favell and pass it on to his sons was called after a medieval type of horse – ‘fallow coloured’.

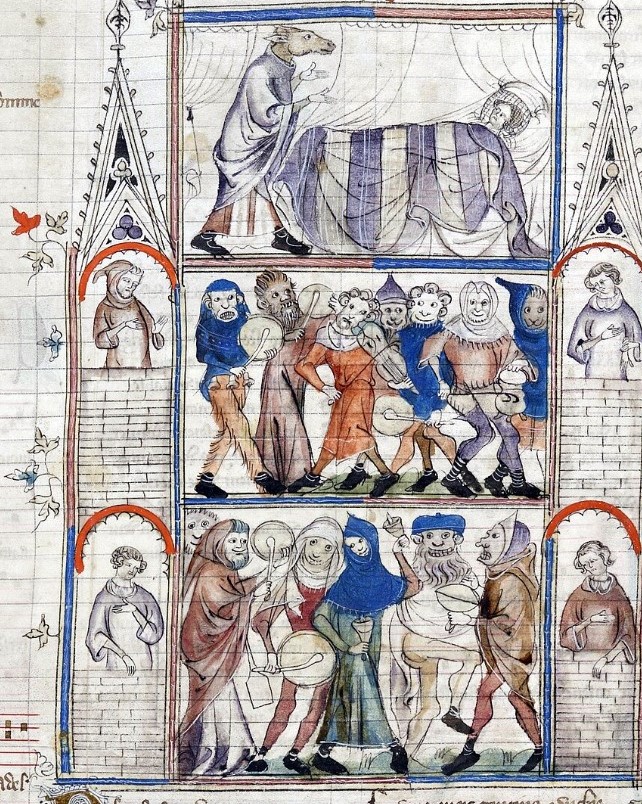

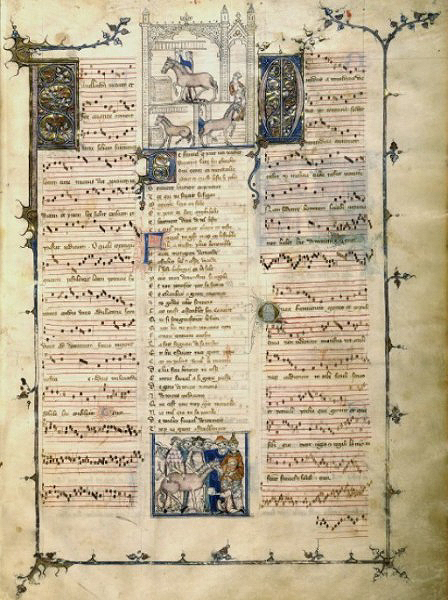

Favell, the ‘dun’ horse (dun is an old name for ‘Fawn’) was a proverbial character known for his evil ways and characteristics. The tale of Favel or Fauvel (French for ‘fallow coloured’) originated in France, but at the time the English Crown owned a great part of that country and many Englishmen of Norman descent still spoke French as their main language.

The expression ‘to curry favour’ is a garbled version of the medieval phrase ‘to curry Favel’ meaning to associate themselves with this epitome of all vice. ‘Curry’ is an old name for ‘grooming’.

A French tale called “Le Roman de Fauvel” was current in educated circles in England shortly after its appearance in 1316, closely followed by a musical version. Ordinary people had already heard the tale and the surname Favell or Fauvel was already in use by our family before the ‘Roman’ appeared.

Every letter of Fauvels name was given an appropriate label: –

F = Flaterie: Flattery or deception

A =Avarice: Greed of every description: fame, wealth, political power. In a portrait of Fauvel he is dressed in fine clothes and wears a crown.

V = Vilanie: Villainy

or

V = Variete: Double dealing, trickery

E = Envie: As well as envy it implies covetness

L = Lachete: Cowardice

In Latin, scholars talked about Favell andii Vicium “the vice of Favel”, which was the subject of a popular song in the musical version of the tale, still available on CD.

“In the year 1310 manuscript copies of a scurrilous satirical poem, the Roman de Fauvel, began circulating around Paris. Corrosive, pitiless, the poet, a mid-level government functionary named Gervais de Bus, attacked what he saw as the pervasive corruption of society’s institutions — both church and state — and of the men who wielded power within those institutions. The poem’s central metaphor for moral rot and decadence was a fallow-coloured horse named Fauvel, symbol of everything wrong with France, her society, and her system of governance”

Richard I of England, and hopefully of France, when he was attempting to conquer, rode a horse into battle which he called Fauvel, as a bitter joke against his enemies, particularly his brother John who was attempting to betray him and take the English throne.